Gimmick Infringement Volume 1: The “Do Call It a Comeback” Edition

Greetings, and welcome to the inaugural edition of Gimmick Infringement, a feature wherein we take a look at one iteration of a gimmick match available on the WWE Network (sorry, this author can’t afford all the streaming services on an American teacher’s salary). Some are iconic for their success, others for the extent to which they flopped, and some just...happened.

We defined a "gimmick match" as, in any way, adding a rule/stipulation to or removing a rule from a match, changing the physical environment of a match, changing the conditions which define a "win", or in any way moving past the simple requirement of two men/women/teams whose contest must end via a single pinfall, submission, count-out, or disqualification.

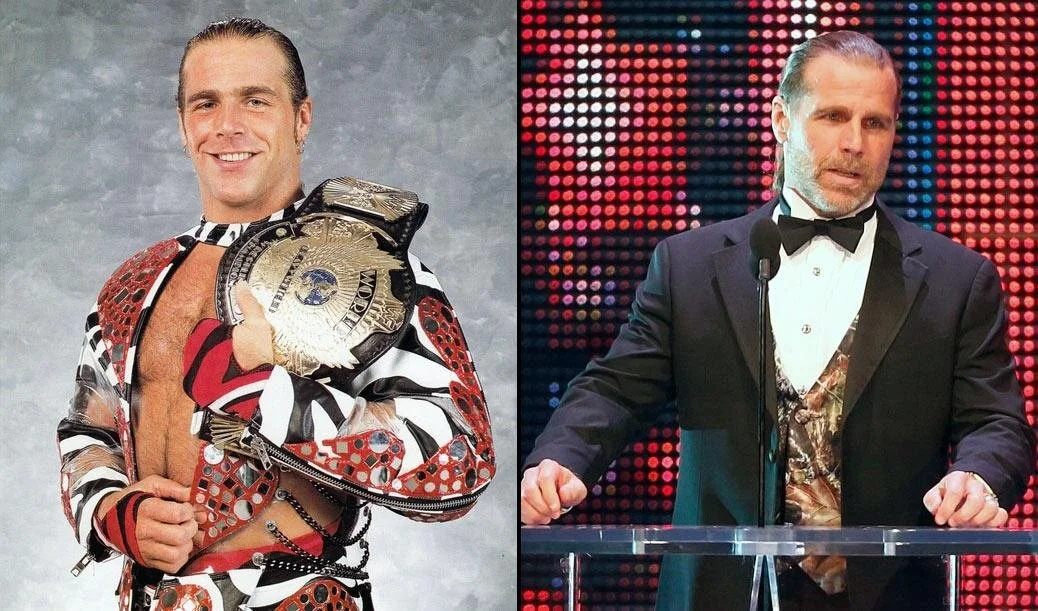

This month, let’s celebrate having a new home with Kefin and Jo on How2Wrestling.com by looking at one of the most memorable comeback matches this century when Shawn Michaels returned from his early retirement to battle Triple H in an unsanctioned street fight at SummerSlam 2002!

A Tale of Two Heartbreak Kids

Understanding this match first requires understanding that Shawn Michaels before the turn of the millennium and after it are two wildly different human beings, while still very gifted performers. It is my earnest opinion that, when the time undoubtedly comes for How2Wrestling to cover The Showstopper’s legendary career, Shawn Michaels up to WrestleMania XIV and Shawn Michaels SummerSlam 2002 onward should be two separate episodes (my suggestion: How2PillShawn and How2JesusShawn).

My interest in professional wrestling began in late 1995 with an Undertaker VHS called He Buries Them Alive, which compiled some of his highest-profile matches from 1994 like his return match against the fake Undertaker at SummerSlam and his casket match against Yokozuna at Survivor Series. This tape showed me a whole new world of entertainment I never knew existed and was the perfect mix of outlandish, colourful, hard-hitting, scary, and silly that wrestling hits when at its best.

Whilst The Deadman is responsible for my first foray into The Business, the reason I stuck around was Shawn Michaels; who, after WrestleMania XI, had turned babyface for the first time since disbanding his tag team, The Rockers, in 1991. This being before WCW brought cruiserweight action into American living rooms, The Heartbreak Kid’s flash and high-flying style was unlike anything I’d seen in my limited wrestling experience thus far.

Big men like The Undertaker, King Mabel, and then-champion Diesel (Kevin Nash) dominated the top of the card that summer, and Bret Hart was presented as the elder statesman who ruled the mat with a serious and precise style; the rest of the players on the roster were outlandish caricatures of clowns, cowboys, pirates, country singers, race car drivers, and, of course, a dentist.

Shawn Michaels was different; like Hart, he didn’t have a “character” as much as he was just a persistent and plucky underdog fighting with every ingenious (but still within the rules) move he could muster to overcome the challenge of dastardly heels like Sycho Sid and Owen Hart. He was the bully-defeating hero who proved to a foster kid from Baltimore that good, eventually, can triumph against evil. In fact, when The King of Harts famously sent Michaels to the concussion ward with an enziguri on Monday Night RAW, 10 year-old me may have shed more than a few tears (and 12 year-old me DEFINITELY cried when Shawn “lost his smile” in 1997).

The backstage Shawn Michaels, however, was less plucky underdog and more hard-partying self-aggrandiser; by WrestleMania XIV in March of 1998, he had only one true friend in the WWF (Paul Levesque, also known as Hunter Hearst Helmsley), a broken back, and a massive addiction to painkillers. Partly out of stubbornness, and possibly partly out of fear of how backstage enemies like The Undertaker would respond if he refused, Michaels masked his crippling back pain with enough prescription drugs to kill Elvis in order to drop the WWF Championship to Stone Cold Steve Austin in the main event match before officially retiring from everyone’s favourite pretend sport.

He would pop up sporadically afterwards in various onscreen non-competitive roles, taking on colour commentary, hosting duties, and even a few stints as an on-screen authority figure, but none of these lasted very long due to Michaels’ addictions and abrasive personality making him an inconsistent, but entertaining employee at best, and impossible to work with at worst. By many people’s recollections, for instance, Michaels was backstage at WWF RAW the night that Vince McMahon purchased his former rival company WCW, but was so high on various pills, and possibly drunk as well, that he passed out in an office and was locked in there for the duration of the show at the insistence of either Helmsley, Undertaker, or Vince himself (depending on whose account you read).

Michaels detailed in his second book (which was about 40% wrestling, 40% Jesus, and 20% hunting) how his own son began to notice his dad was “sleepy” or “angry” at different times, and it was this epiphany that led Mr. WrestleMania to seek a complete break from drugs and alcohol to begin life as a born-again Christian. At this time, too, Michaels had his own wrestling school, training the likes of Bryan “Daniel Bryan” Danielsen, who mentions in his own autobiography how Michaels occasionally took a much more hands-on role in the training than HBK’s mother (and business manager) would have preferred, leading many in his classes to conclude that Michaels might have an itch to return to the ring.

The Return

Nash reintroduced Michaels to WWF audiences in the spring of 2002 as the new leader of the resurrected (and massively watered down) New World Order; at that same time, Helmsley was floundering in a lacklustre babyface run which started with a white-hot return from his legendary quadriceps tear, then slowly fizzled out after losing the WWF Undisputed Championship to Hulk Hogan. The NWO was sputtering, as Scott Hall found himself unemployed due to his drinking while Nash suffered a quad tear of his own, and Helmsley was running on fumes as a good guy by the King of the Ring pay-per-view, which only compounded his babyface problems by bringing back The Rock as the company’s top face.

Michaels begged Helmsley to join the NWO, and Helmsley resolutely refused; trying a different tack, the Heartbreak Kid disbanded the New World Order and said if he and The Game were to reunite, it could only be under the banner they carried together in 1997 and 1998: D-Generation X. The two degenerates embraced their past, and much crotch-chopping and gyrating to the iconic DX theme ensued, before The Game punctuated his trademark Michael Buffer parody with a brutal Pedigree to his alleged best friend.

In later instalments, Helmsley absolutely battered, bloodied, and brutalised Michaels, saying The Heartbreak Kid was too weak, too old, and too washed up to lead Helmsley as he did four years prior. Michaels followed up with an intense promo wherein he feigned falling to the ground in injury, only to kip-up like the Showstopper of old and vow that he would make The Game regret doubting HBK at SummerSlam. The match was on but, as NXT did with Johnny Gargano and Tommaso Ciampa, Michaels’ kayfabe status as “not under contract” meant that he had to sign away any and all rights to liability or injury compensation.

The Rules

Whether sanctioned or unsanctioned (in kayfabe), a street fight in WWF/E typically denotes a match where the only methods of victory are pinfall or submission, which must occur inside the ring. Eric Bischoff, RAW’s then-GM, announced the match would be non-sanctioned, with World Wrestling Entertainment not responsible for any harm visited upon either man. This was due to the fact that, both onscreen and in real life, Michaels was not a regular contracted performer (and, backstage, this match was seen as a one-time-only return to redeem Michaels’s image with his family and former coworkers).

The Match

Michaels’s entrance is on the subdued side, at least by HBK standards; the pyro and confetti are there, but he trades the showy dancing and acrobatics for a stoic walk to the ring, and his flashy outfits for a simple pair of jeans, cowboy boots, and a Philippians 4:13 t-shirt. It’s a distinct character, and personal choice to show that Michaels had completely changed his life and was not the man who screwed Bret Hart, Shane Douglas, and/or Sunny. However, this happening at least a decade or more before stretch jeans became widely available for men, I have no idea how his choice of ring gear could be anywhere near comfortable (this comment brought to you by my extensive Lee Extreme Motion collection).

Triple H is in the early stages of the era in which he does his best to ape Ric Flair in 1988, opting for a clean-shaven look that breaks from the beard, leather, and denim that had defined the first two-thirds of his 2002 year. The match starts with nothing short of pure fan service, as Shawn hits signature taunts, planchas, and quick strikes to pop the crowd. Peak nostalgia comes when Michaels smacks Helmsley with a trash can lid from the outside before “skinning the cat” a la his Royal Rumble-winning reentry to tease an early end to the match. Triple H ducks a Sweet Chin Music to nail an emphatic backbreaker which looked devastating at the time, but in retrospect is a nod to us, the viewer, that Shawn Michaels is well and truly healed.

Helmsley works the back, and the crowd, with elbows and strikes punctuated with old DX taunts. He adds a chair, much to JR’s indignance, and squashes an attempted Michaels comeback with his signature facebuster before DDT’ing his old running buddy onto the chair. HBK’s blood begins to flow, and Helmsley ups the ante by whipping Shawn with Shawn’s own belt hard enough to dislodge its Texas-sized buckle.

Trips takes an extended powder to find his sledgehammer while HBK dutifully sells in the ring. Shawn begins to fire back up, but his momentum is quickly squashed with a whip to the turnbuckles and an abdominal stretch; the stretch sets up a fun bit of business where The Game grabs the top rope for that magical pro wrestling “leverage,” and referee Earl Hebner explodes in a fit of rage, arguing with a backing-off Helmsley that the official has “had enough” with Triple H’s litany of bad-guy tactics in the match.

Shawn fights off a superplex attempt to set up an elbow drop, but The Game shoves Hebner to the ropes to knock his opponent down, setting up a hard chair shot to the back and a gnarly backbreaker to the open steel chair. The latter manages to draw a halfhearted “holy shit” chant and a two-count. A sidewalk slam on the chair sets up a series of increasingly more frustrated two counts, and the crowd is swelling louder and louder with each kick out, before they explode when Michaels counters a Pedigree attempt with a forearm to the groin. As The Game stalks his opponent, chair in hand, Mr. Wrestlemania pops out of the corner with a superkick to the chair; though Shawn is too tired to capitalise on the move, it does manage to bloody his rival.

Crowd firmly in his favour, Shawn starts playing the hits, with his forearm-and-kip-up followed by hard chair and trash can shots, before bringing the belt back into play while the crowd chants for tables (and while Helmsley’s blood pools on the outside mats). The announcing hits a fun meta note as HBK takes Spanish announcer Hugo Savinovich’s boot to nail The Game, prompting a fun bit of “heel for a heel” wordplay from King and JR.

Speaking of playing the hits, Shawn retrieves from under the ring his bread and butter from his first WWF run: a ladder, which he uses to smash Helmsley’s face and ribs, before slingshotting the future COO into it for a two count. The Game steals a Michaels classic by baseball sliding into the ladder to kick it into Michaels’s ribs, leaving a sick-looking bruise. Michaels drop toeholds a stairs-wielding Helmsley before opting to grant the Nassau Coliseum’s wish for tables. Putting Triple H atop one at ringside, Michaels dives from the top rope with a vintage HBK splash to drive Helmsley through the table, earning a much more robust chant for deified feces.

The ladder comes back into the ring for a Shawn Michaels elbow drop from the second-highest rung (“I love each and every one of you,” he tells the crowd in a genuinely touching moment) before setting up for the superkick. Helmsley blocks to set up the Pedigree yet again, but gets rolled up for an unexpected three count. Shawn gets very little time to celebrate before Triple H retrieves Chekhov’s Sledgehammer to attack HBK’s back, leaving Michaels to be stretchered out of the ring. “Do you have no heart? Do you have no soul?” JR rages as Helmsley laughs in retreat.

My Rating

I have, and had at its first airing, lots of mixed feelings about this match.

Former (and current) creative team member Bruce Prichard noted that the plan was for this match to be a one-off return just for Shawn to prove to himself and his family he still had “it” in him (not unlike Goldberg’s brief 2016-2017 streak against Brock Lesnar and Kevin Owens); the fan reaction to the match and Shawn’s own assessment of how he felt after the contest made the company consider keeping the run going a little longer (which, of course, turned into a span of almost a decade featuring two of WWE’s top ten matches of all time, by the company’s own reckoning).

Whether an extended stay was in the cards at the time or not, having Helmsley “get his heat back” with the sledgehammer attack after the bell shows a massive problem WWE suffered in 2002: they were fully unable to go “all-in” on anything. The same summer this match happened, The Undertaker was a biker bully heel who tormented most of the roster (but sold punches from Hogan and The Rock like a 1980s caricature of a bad guy), Brock Lesnar was beginning his rise to the main event by absolutely murdering his way through the undercard (before barely squeaking by a pretty dominant Test in the first round of the King of the Ring tournament).

As with their refusal to really let Undertaker and Lesnar dominate the way a monster heel needs to, WWE refused to let HBK really win this contest, which cheapens so much of the emotion and drama its two competitors managed to build. If shock value or crowd reaction were the reason to flip the script here, one has to wonder why the company didn’t opt to do it on the following night’s RAW from Madison Square Garden, home of some of WWE’s most ardent non-WrestleMania week crowds.

The match is excellent, and really draws in the live crowd and those of us on the couch with a story familiar to fans of any sports movie featuring the grizzled vet giving it “one last go”. Both men are giving and game, and string together some truly clever and enjoyable sequences to tell a really compelling story. Shawn showing his love for the crowd is truly touching, and it’s always inspiring to watch performers who really enjoy what they do and who they do it for.

Again, though, in the context of the time, this is also one of its biggest weaknesses. From his return to pay-per-view after quadriceps tear at the 2002 Royal Rumble through much of the ‘aughts (and beyond), Triple H had a reputation for having three types of PPV matches: pretty standard middle-of-the-road matches (vs. Booker T or Kane), absolute “can’t be bothered” stinkers (vs. Scott Steiner or Kevin Nash), and bona fide classics (vs. Shawn Michaels, Shawn Michaels, and Shawn Michaels and Chris Benoit). Wrestling Shawn Michaels in this time period made HHH look transcendent in a way only Mick Foley was able to before (more on that next month), and one has to wonder whether the reason is The Showstopper’s preternatural performance abilities or Helmsley choosing to elevate his game for his best friend and no one else.

The match plays a lot like the setlist Iron Maiden plays on their current Legacy of the Beast Tour: it hits all the right notes and all the great spots that made fans fall in love with the performers in the first place, and takes a “greatest hits” setup in a fun new direction. Both let fans who grew up on the featured performers’ body of work enjoy what could be a last hurrah as age and health (Shawn’s broken back and, for Maiden, Bruce’s twenty-teens battle with cancer) make retirement (or re-retirement, in Shawn’s case) loom large.

The difference, though, is that Maiden is a brand built on maximising its strengths for the fans’ enjoyment. In 2002, neither WWE nor Triple H were willing or able to do the same. The match is great by itself and out of context, and, truly, if you were not watching in 2002, this match is absolutely worth a watch as its action holds up really well despite being old enough to vote in this year’s presidential election. However, to keep the magic alive and to be able to really appreciate the near half-hour Helmsley and Michaels tell their story, you have to ignore most of the rest of Helmsley’s 2002, especially the two minutes right after he’s pinned in this match.

Rating: 9/10 for the match itself, but 7/10 with the shenanigans after the match (and the rest of 2002) factored in.