A Brief History of All Things Lucha Libre, Pt 1

I’ll start this piece off with a bold claim: Lucha Underground is the best weekly wrestling product going around these days. It is exactly what you’d expect to see if someone told you that Robert Rodriguez of Machete and El Mariachi fame had decided to create a wrestling promotion that would bring the masked men and women of Mexican Lucha Libre to an American and Global audience.

Lucha Underground’s approach to storytelling is nothing short of revolutionary and almost unique in the world of wrestling. It is a world of Legendary Battles between Lucha Libre’s past, present and future. Lucha Underground is a world where you will see wars waged weekly between Luchadores (the men) and Luchadoras (the women) including an Indestructible Zombie King and his Ghoul Army, a Mad Butterfly Woman, an Immortal Phoenix Warrior, a time travelling Power Ranger bringing prophecies of returning Aztec Gods and AN ACTUAL DRAGON.

Lucha Underground is the best weekly wrestling product going around these days.

It has been creating a solid buzz amongst fans (the Believers as commentators Matt Striker and Vampiro call them) since day one; especially amongst the “smart” corners wrestling fandom. Now, as the show builds towards the climax of its second season I’m sure there are more than a few people out there wondering where to start with the show, and more generally how to wrap their heads around the rich traditions of Lucha Libre. My goal then, over the next couple of thousand words or so, is to provide a broad overview of the storied history of Lucha Libre; its origins, its traditions and its key figures. Then a look more specifically at how Lucha Underground is revolutionising it and wrestling more generally for the 21st Century.

Lucha Libre, or at least the iconic image of the Luchador mask, has been embedded in pop culture for at least the last 20 years. The actual origins of Lucha Libre are shrouded in mystery, debate and conjecture and probably not that important in the context of this article. The first key milestone on the road to what we now call Lucha Libre was the creation of the EMLL, the Mexican Wrestling Enterprise in 1933. The EMLL, now the CMLL, has been promoting Lucha Libre wrestling since that day some 85 years ago – making it the oldest continuously running wrestling promotion in the world.

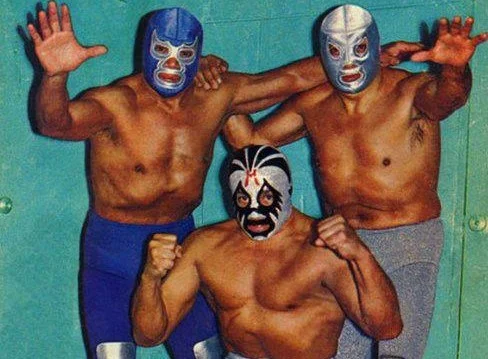

The iconic image of the Luchador mask has been embedded in pop culture for at least the last 20 years.

The introduction of Masks and Masked wrestlers which have come to be synonymous with Lucha Libre followed soon after with the introduction of wrestlers like La Maravilla Enmascarada (the Masked Marvel) and El Murcielago Enmascardo (the Masked Bat). These masked men of muscle mystery were quickly embraced by the Mexican public firmly cementing the tradition, honour and mystique of the mask as the foundation of Lucha Libre and Luchador culture.

It’s worth noting that, north of the border in New York, this same era was giving birth to Superman, Batman, Captain America and the Golden Age of Superhero comics. I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to draw clear line from the square jawed two fisted brand of justice delivered by those Caped Crusaders and the larger than life dramas being contested by the masked Men of Lucha Libre. The Great Depression left people both sides of the Gulf of Mexico hungry for heroes and a modern mythology which would quench their thirsts for action, adventure and justice.

There is no greater proof of this than the rise of El Santo, the Santo, the Man in the Silver Mask and arguably the biggest star that wrestling has produced anywhere in the world, ever. The word Icon is thrown around a lot these days, to the point where it has lost some of its meaning. But there is no truer icon in the world of Lucha Libre than El Santo. The name, the look, the character, the commitment to never being seen without a mask are indelibly etched into the DNA of Lucha Libre. El Santo was the platonic ideal of what a Luchador should be, from his debut in 1942 to his death in 1984.

El Santo was to wrestling what The Beatles were to pop music; an iconic transcendent figure who came to define their chosen profession in the eyes of the world’s public. El Santo was more than just a wrestler. He was a folk hero, a cultural force, and the first wrestler to transcend the world of the squared circle to conquer television, comic books and cinema.

El Santo was the ultimate Technico, the Lucha Libre term for a baby face or good guy wrestler. El Santo, along with the legendary Rudo, the heelish Blue Demon and family patriarch Gory Guerrero, would define the foundational elements of Lucha Libre. The masks and costumes, the high flying moves and the epic stories of good versus evil where combatants would wager their honour, their mask or their hair on the outcome of a match would all take shape as the art of Lucha Libre evolved.

They would tell stories in and out of the ring that would provide the blueprint for the next 70 years of Lucha Libre and change the world of wrestling irrevocably.

Over time Lucha Libra would fall in and out of favour in Mexico just as wrestling ebbs and flows with tides of mainstream popularity all around the world. But it never really managed to gain a substantial footing in the broader wrestling landscape of the USA. There were wrestlers like Mil Mascaras, Dos Caras, Dr Wagner and the Guerrero brothers, Hector and Chavo Senior who had some success working territories in the Southern American states. There were masked wrestlers in American promotions like Mr Wrestling, the Killer Bees or the unimaginatively named Masked Superstar, but none of them really captured the true spirit and energy of Lucha Libre.

That would all change in 1994 when Eric Bischoff, the mastermind behind Ted Turner, backed Atlanta based wrestling powerhouse WCW. Partnered with the Mexican promotion AAA they brought their event When Worlds Collide to an American PPV audience. AAA, (Assistance, Assessment and Administration) was a breakaway promotion from the Old Guard of the CMLL looking to establish a new vibrant, more energetic brand of Lucha Libre to a wider audience across North America.

When Worlds Collide featured a crop of exciting second and third generation Luchadores such as La Parka, Konnan and Psicosis, with up and coming American stars like Chris Benoit (wrestling as the Pegasus Kid) and 2 Cold Scorpio and legends like Tito Santana and El Hijo del Santo (the in story and IRL son of the iconic El Santo). It brought a style of high flying, jaw-dropping, death defying moves that must have struck wrestling fans like a bolt of lightning from Wrestling Heaven. After decades of watching wrestlers rarely leave their feet or getting disqualified for going over the top rope, moves like missile drop kicks, springboards and the hurricanrana were nothing short of a revelation. It was also the first opportunity for an American audience to witness to future legends in Rey Mysterio Junior and Eddie Guerrero play their craft inside the squared circle.

It’s no understatement to say that without these influences, Lucha Underground would not exist. The Lucha Libre style which revolutionised American Wrestling over the course of the next 20 years would likely never have been seen outside a select segment of the wrestling community. There are some in the wrestling fandom that believe Extreme Championship Wrestling saved wrestling from itself in 1995 and that all should bow down and accept Paul Heyman as their wrestling messiah. Your mileage on this may vary but there is no denying that Heyman was quick to capitalise on the exposure that When Worlds Collide gave to many of these Luchadores and bring them to his still developing ECW.

Heyman was keen to bring wrestlers like Chris Benoit, Dean Malenko, Rey Mysterio Junior, Psicosis, 2 Cold Scorpio, Eddie Guerrero and even a young Chris Jericho into the ECW Kool Aid Cult and unleash them and their high flying, hard hitting style on his rabid fans in the ECW Arena. Although they would all only remain in the land of Extreme for a year before heading south to Eric Bischoff’s World Championship Wrestling (WCW), it was clear that the wrestling landscape had changed forever.

The early to mid-90s were a transitional period for wrestling. The WWF, now WWE, moved away from lumbering muscle bound titans like Hulk Hogan, the Ultimate Warrior and Lex Luger while the WCW tried to outgrow its Southern Good Old Boy Rasslin’ Roots to become a national, if not global wrestling brand.

Luchadores and Lucha Libre were at the forefront of this, beamed every Monday night into the homes of millions of American families as part of WCW’s Monday Nitro broadcast. As Eric Bischoff tried to present WCW as an alternative to their rivals “Up North”, the Cruiserweights (as the Luchadores were labelled in WCW) were at the forefront of that revolution. Some would argue that the Cruiserweight Division was the only reason to watch WCW programming between 1996 and 1998 as the novelty of Hulkamania’s return wore off and the endless n.W.o storylines began to hover like dark clouds on the company’s horizon.

Like many things in WCW the wheels began to fall of the wagon of the Cruiserweight division in 1999. Luchadores, including Rey Mysterio Junior, were unmasked in meaningless matches to make them more marketable to non-Latino audiences, and the Cruiserweight title was at one point demoted to joke status, held by Oklahoma, WCW’s parody of WWF announcer Jim Ross.

After WWF bought WCW in 2001 it made several attempts to revitalise the Cruiserweight/Lucha Libre style with champions ranging from great wrestlers such as Rey Mysterio Junior, Chavo Guerrero Junior and Yoshihiro Tajiri, to the downright ridiculous such as Hornswoggle, who was the last WWE Cruiserweight Champion 2007. Despite the death of the WWE Cruiserweight title, crossover Lucha Libre stars like Mysterio, the Guerreros, Tajiri, and later Sin Cara, Kalisto and Alberto Del Rio (himself son of the legendary Luchador Dos Caras) continued to enjoy varying levels of success throughout the WWE.

There were a few failed attempts to transplant Lucha Libre from Mexico to the USA with promotions like Lucha Libre USA largely failing to capture mass interest. It took the combined forces of reality TV powerhouse Mark Burnett (responsible for shows like Survivor, The Apprentice and The Voice) and maverick Mexican America filmmaker Robert Rodriguez to usher in a new golden age of Lucha Libre in America with the 2015 birth of Lucha Underground.